By Clarence Lucas

© Clarence Lucas

Musical Courier, 1 October 1931![]()

An Epoch-Making Composer Who Died of a Broken Heart— His Operatic Masterpiece Failed, as Did His Domestic Life

Berlioz began his opera, Les Troyens, in 1856. In 1863 it was put in rehearsal, but proved to be too long. It was cut in two and the two sections were re-written as Prise de Troie and Les Troyens à Carthage. The second opera was finally produced at the end of 1863, but failed for lack of support or interest after the twenty-first performance.

Berlioz never recovered from his disappointment. He died without hearing the first of the two operas. The second opera, Les Troyens, was revived at the Grand Opera House last November, but again the Parisian public heard it without enthusiasm. It 1acks the lyrical beauty of the older operas, and the harmonies and orchestral effects are not new and strange to modern ears. This Berlioz music is never as commonplace and trivial as many pages of Gounod’s Faust are; and it falls far short of the harmonic richness and contrapuntal complexities of Wagner’s Meistersinger. Yet Wagner’s ponderous musical comedy, and Gounod’s sentimental tragedy were rapturously received at the same opera house that witnessed the revival of Berlioz’ historical romance later in the week.

Last December Gabriel Pierné, conductor of the Colonne

Orchestra of Paris, celebrated the hundredth anniversary of the composing and

first performance of the Symphonie Fantastique, in which Berlioz himself played

the tympani part when the work was produced in the concert hall of the old

Conservatoire. This was one of the first scores the then young Liszt transcribed

for the piano. The Countess d’Agoult mentions it among the “new

compositions of musical romanticism.”

Last December Gabriel Pierné, conductor of the Colonne

Orchestra of Paris, celebrated the hundredth anniversary of the composing and

first performance of the Symphonie Fantastique, in which Berlioz himself played

the tympani part when the work was produced in the concert hall of the old

Conservatoire. This was one of the first scores the then young Liszt transcribed

for the piano. The Countess d’Agoult mentions it among the “new

compositions of musical romanticism.”

Heine thus describes the first performance:

“What a pity that Berlioz had his vast locks cut,—those bristling, antediluvian hairs which rose from his forehead like a forest on the slopes of a precipitous rock. That is how I saw him for the first time six years ago, and as such he will remain forever in my memory. At the Conservatoire a grand symphony of his was played,—an odd, nocturnal piece, occasionally brightened by a woman’s robe, sentimentally white, which fluttered here and there,—or by a sulphur-colored flash of irony. The best part of it was the witches’ orgies, when the devil says the mass, and the music of the church is parodied with the most terrible and outrageous buffoonery. It is a farce wherein all the hidden vipers, which we harbor in our hearts, rise and joyfully hiss.

My companion in the box, a talkative young man, showed me the composer at the far end of the hall in a corner of the orchestra, playing the tympani; for those are his instruments. “Do you see that large English woman in the stage box? She is Miss Smithson; and Monsieur Berlioz has been dying for love of that woman for three years. We owe this savage symphony we hear today to that passion.”

In fact, the celebrated actress from Covent Garden was sitting in the stage box. Berlioz kept his eyes fixed on her, and whenever his glance met hers he thumped his drum like a madman. Meanwhile Miss Smithson has become Madame Berlioz, and her husband has had his hair cut. When I heard the symphony again this winter at the Conservatoire, he played the tympani as usual in the back row of the orchestra. The large English woman was again in the stage box, and once more their glances met. But he did not strike the drum so furiously.”

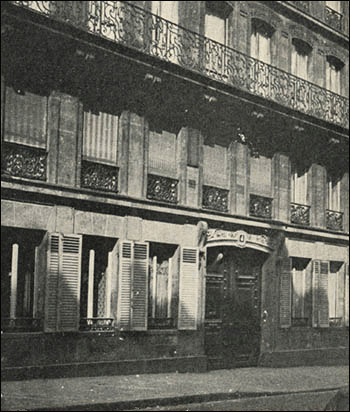

Thirty-three years after the first performance of the Symphonic Fantastique Berlioz was crushed by the failure of his opera. Miss Smithson was dead, and their only son had lost his life at sea. In 1869 the remains of the disappointed composer were carried from 4 rue de Calais to the Montmartre Cemetery and deposited near the thirteen-year-old grave of Heine.

* This article and the pictures that

accompany it have been scanned from a

contemporary copy of the Musical Courier, 1 October 1931, in our own collection. The photograph on the right, taken by Clarence Lucas, is that of Berlioz’s last home at No. 4 rue de Calais, Paris. We have preserved the author’s original spelling,

punctuation, and syntax, but have corrected obvious typographical errors. We

have not been able to contact the editor and publishers of the Musical

Courier.![]()

See also on this site:

Berlioz’s home at No. 4 rue de Calais

![]()

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 8 March 2010.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.

![]() Back to Original Contributions page

Back to Original Contributions page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Contributions Originales

Retour à la page Contributions Originales

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil