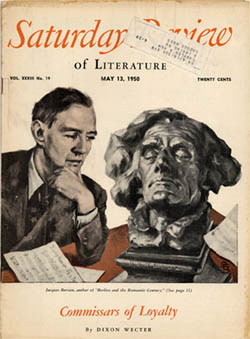

BERLIOZ AND THE ROMANTIC CENTURY

By Jacques Barzun

Reviewed by Robert Lawrence

© Robert Lawrence

Published in

|

BERLIOZ AND THE ROMANTIC CENTURYBy Jacques BarzunReviewed by Robert Lawrence © Robert Lawrence Published in |

|

![]()

MUSIC. The inquiring music-lover in search of exhaustive musical biography will find the lives of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Wagner minutely set forth in compendious, multi-volume works. Hector Berlioz now joins this select company with the publication of Jacques Barzun’s “Berlioz and the Romantic Century.” Any work of this size has its ups and downs but in totality it is clear that Barzun’s “Berlioz” (reviewed below) is of like stature with Thayer’s “Beethoven” or Newman’s “Wagner.” . . . Two months ago [SRL Mar. 25] we noted the appearance of Victor I. Seroff’s new biography of Rachmaninov (the spelling preferred by our reviewer). Hard on its heels comes another book on this composer, this one by John Culshaw, with a more strictly musical approach. . . . Admirers of the wit and sagacity of Donald Francis Tovey will welcome the publication of a posthumous volume of essays, “The Main Stream of Music.”

![]()

BERLIOZ AND THE ROMANTIC CENTURY. By Jacques Barzun.

Boston: Little, Brown & Co Vol. 1, 573 pp. Vol. II, 370 pp. $12.50.

By ROBERT LAWRENCE

HECTOR Berlioz, the one great musical figure to come from nineteenth-century France, vilified in his lifetime and undervalued for fifty years after his death, has of late risen precipitously in general estimation. It is fitting that the recent Berlioz revival in the concert hall should be capped by a study of this stature.

To reveal Hector Berlioz in the perspective of his relationship to the other outstanding Romantics of his time, to establish the composer as the fountainhead of all that has come after him in virtually every sphere of symphonic and operatic music: these have been the twin aims of Jacques Barzun in his new and unusually rewarding biography. As this long recital draws to a close the magnificence of the creator’s personality comes clearly into focus, the figures surrounding him emerge with warmth and humanity. The book, whatever its shortcomings, has been badly needed. Studies in English on the life and art of Berlioz have so far only scratched the surface, and at his best Mr. Barzun, treating a subject obviously congenial to him, commands an impressive range of scholarship and eloquence of style.

Surprisingly enough, it is not the great days of the 1830’s—hailed by the author as the climax of French Romanticism—that emerge with true literary or historical distinction so much as the era of artistic dissolution and decline marked by the advent, a generation later, of Napoleon III. Mr. Barzun is more successful in treating a period he dislikes, outlining it with cold, clear, analytical strokes, than in evoking, with incense-burning references to Stendhal, the young manhood of Berlioz and his early triumphs. In the latter instance Mr. Barzun becomes an almost mystical member of the scene, frequently substituting himself for Hector in an impassioned defense of his subject, discarding the clarity of tone and purpose that should have marked this work throughout. The large outlines of the story are well set. Guided by a mass of historical documents unearthed or translated by the author over a long period of research, one follows the career of Berlioz from his first attempts for the Prix de Rome, marked by the fire and abandon of romantic youth, to the last, exhausted public appearances of his Russian tour forty years later. Through the book like a leitmotiv runs Berlioz’s love of Shakespeare, which was to influence his creative and private life so profoundly. Accompanying every section of Berlioz’s lengthy public span is a chapter analyzing specific musical works of the period. Other correlated pages deal with the composer’s manifold activities as journalist, poet, and critic. His political views, detached but basically liberal, are set forth with some interest. The proportions of the vast book are finely integrated, enclosing the life and works of Berlioz as in a spacious colonnade.

Certainly there have been few figures in the history of music with so fascinating, almost hypnotic, an appeal for the present-day reader as Berlioz. With his life span encompassing roughly the rise and fall of two French empires, he emerges as perhaps the first totally modern mind in music— the man of affairs as well as of notes, a great conductor, concert organizer, writer of distinction. Whatever he touched, in any medium, bore the mark of his volatile, yet strangely sober, personality. Unlike his predecessors Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, he was equipped to challenge the intellectual world on all fronts and make his charge across any field. This basic phase of Berlioz’s gift—its multiplicity in unity—has been admirably detailed by the author.

Less successful is Mr. Barzun’s treatment of the actual scores. He would have us believe that all of music since 1830 has changed its course because of Hector. This is an extravagant claim, based more on hypothesis than on fact. When the author cites the similarity of the opening motive of Wagner’s “Tristan and Isolde” to the “Roméo seul” theme of Berlioz’s “Romeo and Juliet” symphony, he is erring on his own or quoting from a capricious source. The two ideas vary markedly in interval, rhythm, and key. Again, with rumblings of plagiarism in the air, Mr. Barzun charges that the “Eucharist” theme of “Parsifal” was lifted out of the opening of the Berlioz “Requiem.” This is sheer nonsense. One of the two melodies (Wagner’s) is in the major mode, that of Berlioz in the minor; the “Eucharist” motive is diatonic, that of Berlioz semichromatic. What Mr. Barzun, with his indiscriminate handling of musical data, has done is to weaken his case even at moments when it is just. Perfectly true are the assertions that the love motive from “Romeo” lives again in the “Love Death” from “Tristan” and that the shepherd’s famous call in the Berlioz “Fantastique” enjoys a lineal descendant in the third-act English horn solo of “Tristan.” So much is accurate, but Mr. Barzun carries a good thing too far. His chapter on the relationship of Berlioz and Wagner, based on letters and historical documents, is more illuminating. It shows two geniuses, completely incompatible because of their separate missions, making halting and only sparsely successful steps to understand one another.

What Mr. Barzun has minimized is the fact that the expressive range of modern music—as practised by Berlioz and his successors—goes back structurally to the freedom of the last quartets of Beethoven. What Hector brought into actuality, his own distinct contribution, was the use of sound as a component element in the tonal mass, sometimes equal in importance to the basic form of the work itself. The author has aptly traced the descent of this principle from Berlioz through the young Russians (Moussorgsky and his associates) to Debussy and the twentieth century. But, on another front, he has signally neglected the very real influence of Berlioz on modern Italian opera. Boito’s “Mefistofele” is, in many of its pages—notably the “Brocken” scene—almost pure Hector; and it was partially under the influence of this arresting composer-librettist that the last two operas of Verdi, “Otello” and “Falstaff,” markedly Berliozian in their spare yet brilliant treatment of the orchestra, came into being.

This is, then, a “literary” biography with musical analyses which are slight in interest, sometimes debatable, and generally lacking in first-hand authority. Thus, in treating of the “Royal Hunt and Storm” from “Les Troyens,” Mr. Barzun writes: “The beautiful horn calls which emerge toward the middle and blend at the close with a return to the original theme lead to ‘a succession of exquisitely wrought details’ which Mr. B. H. Haggin finds of ‘a startlingly intense loveliness.’”

Almost nowhere does one discover what the author himself deduces from a phrase or a movement of Berlioz, and thereby one’s respect for the book as a direct and authoritative musical source is diminished. That the historical and tonal elements in the biography of a composer can be skilfully blended has been shown by Ernest Newman, Francis Toye, and many others. It is in this department that Mr. Barzun has failed, while excelling in the documentary.

One rather regrettable recurrence of a standard cliché in the new work takes place with almost every passing reference to the operas of Meyerbeer. This composer’s “Robert the Devil,” produced at the Paris Opera in 1831, created almost as much of a revolution at the time in the field of lyric drama and especially of ballet as did the music of Berlioz in the symphonic sphere. Admittedly flawed, often conceived for middle-class taste, these operas will nevertheless be restudied some day at first hand, with proper light thrown on their credit as well as debit side. Certainly no historian of the period should dismiss the great moments of “Les Huguenots” and “Le Prophète” so cavalierly as does Mr. Barzun, even though the works themselves found little favor with Berlioz in his capacity as critic.

There is a quarrelsome overtone to the book, undoubtedly prompted by the neglect and misunderstanding which unjustly surrounded Berlioz’s music for years. Instead of giving us the positive essence of Hector’s art— his sweet distillation of sadness, his amazing use simultaneously not so much of several contrapuntal lines as of diverse planes of musical experience—Mr. Barzun has offered a running argument on a subject whose worth has been established for the past decade. In short, the new biography is erratic and uneven, but, as its own positive merit, offers a monumental brand of scholarship. The work was twenty years in the preparation and writing, and much new material of interest to admirers of Berlioz and to music-lovers in general may be found in its pages.

Robert Lawrence, conductor of the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra, is an occasional commentator on the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts.

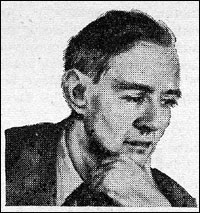

THE AUTHOR: “I make no pretense to being a musicologist,” says

Jacques Barzun of the biography reviewed [above]. Nevertheless, he doesn’t

remember a time when the language of music wasn’t familiar to him. To

any criticism of his observations on Berlioz’s works he has only this to

say—with unruffled tolerance, in a slightly British-accented voice—,

“No person interested in music ever agrees with a statement another

makes about a particular piece of music.” Barzun, however, has

“an inclusive, comprehensive interest in all the arts,” a

catholicity which has manifested itself for many years in erudite

articles. Usually identified as a “cultural historian,” he

prefers to be called simply “a student of cultural history.” As

the former, then, he chose Berlioz to exemplify the ideas, and arts of the

nineteenth century—or, rather, “Berlioz selected himself through

being an encyclopedic mind and therefore having to do with every kind of

issue, enterprise, and tendency of the period.” The resultant two

volumes of assiduous scholarship have taken five intensive years, although

notes on them have been accumulating for more than twenty. He writes most

nights until early morning and a few hours later has to be uptown at

Morningside Heights, where since 1945 he has been a professor of history.

The French-born son of the author Henri Martin Barzun, and himself the

father of three, he had just been graduated from Columbia, in 1927, when

he began teaching, and now, looking a singularly young, lean, and ascetic

forty-three, finds himself “one of the older generation in the

University faculty.” In 1933, by then an American citizen, he went

abroad to amplify his doctorate into his first book, “Race.”

Since then he has published, among others, “Of Human Freedom,”

“Darwin, Marx, Wagner,” and “Teacher in America.”

“Maybe,” he says, “in my old age, like Santayana, I’ll

write a novel—‘The Latest Puritan,’ or something.”—R. G.

THE AUTHOR: “I make no pretense to being a musicologist,” says

Jacques Barzun of the biography reviewed [above]. Nevertheless, he doesn’t

remember a time when the language of music wasn’t familiar to him. To

any criticism of his observations on Berlioz’s works he has only this to

say—with unruffled tolerance, in a slightly British-accented voice—,

“No person interested in music ever agrees with a statement another

makes about a particular piece of music.” Barzun, however, has

“an inclusive, comprehensive interest in all the arts,” a

catholicity which has manifested itself for many years in erudite

articles. Usually identified as a “cultural historian,” he

prefers to be called simply “a student of cultural history.” As

the former, then, he chose Berlioz to exemplify the ideas, and arts of the

nineteenth century—or, rather, “Berlioz selected himself through

being an encyclopedic mind and therefore having to do with every kind of

issue, enterprise, and tendency of the period.” The resultant two

volumes of assiduous scholarship have taken five intensive years, although

notes on them have been accumulating for more than twenty. He writes most

nights until early morning and a few hours later has to be uptown at

Morningside Heights, where since 1945 he has been a professor of history.

The French-born son of the author Henri Martin Barzun, and himself the

father of three, he had just been graduated from Columbia, in 1927, when

he began teaching, and now, looking a singularly young, lean, and ascetic

forty-three, finds himself “one of the older generation in the

University faculty.” In 1933, by then an American citizen, he went

abroad to amplify his doctorate into his first book, “Race.”

Since then he has published, among others, “Of Human Freedom,”

“Darwin, Marx, Wagner,” and “Teacher in America.”

“Maybe,” he says, “in my old age, like Santayana, I’ll

write a novel—‘The Latest Puritan,’ or something.”—R. G.

* This article has been transcribed from a contemporary copy of the Saturday Review of Literature, 13 May 1950 (Volume XXXIII. – Number 19, pp. 11-12) in our collection. We have preserved the author’s original spelling, punctuation, and syntax, but have corrected obvious type-setting errors.![]()

We have not been able to contact the editor of this issue of the Saturday Review of Literature, which has ceased publication.

The Hector Berlioz Website was created by Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin on 18 July 1997; this page created on 1 July 2008.

© Monir Tayeb and Michel Austin. All rights of reproduction reserved.![]() Back to Original Contributions page

Back to Original Contributions page

![]() Back to Home Page

Back to Home Page

![]() Retour à la page Contributions Originales

Retour à la page Contributions Originales

![]() Retour à la Page d’accueil

Retour à la Page d’accueil